Teaching Statement

The Spirit of Learning

I believe that learning is fun, exciting, and rewarding; it opens eyes to the world, hearts to other people, and doors to the future. Over the past few years, I have had the privilege of designing my own learning experience and working with great teachers in psychology, anthropology, acting, persuasion, and organizational behavior. Genuinely inspired by my educational experiences, I would like to pass on the same spirit of learning to my students. I hope that students in my class will not only gain knowledge and skills in research and thinking, but cultivate curiosity about social phenomena and underlying mechanisms as well. Most importantly, my goal is that students gain a deeper understanding about their interests and passion, which will motivate them to continue self-guided learning long after graduating from my class.

The ability to conduct self-guided learning is especially critical to this generation of students. The rapid pace of technological advancement constantly poses new sets of challenges to our society, which go far beyond the issues researchers have investigated in the past. And for many problems, we do not have established theories, methods, or tools to solve them. As I expect my students to take on leading roles in various segments of our society, it is critical for them to learn how to effectively guide their own learning and solve unprecedented issues based on existing knowledge, skills, and available methods. To inspire them to become self-guided life-long learners, my teaching philosophy focuses on project-based learning, an interactive learning environment, and multi-disciplinary teamwork.

My Teaching Approach: “Leading with Empathy” as an Example

In Summer 2015 and 2016, I implemented my ideals of teaching and learning in my pre-college course at the Brown Leadership Institute, entitled “Leading with Empathy in the 21st Century”. This was a new course I developed and taught independently. Over two weeks in each summer, 25 high school students from all over the world spent 5.5 hours each day in my class to study the science of empathy and to cultivate empathy in themselves and in our interdependent society. The course consisted of three major components. The first one was academics: Students learned important concepts, theories, and research paradigms on empathy and leadership from social psychology and social neuroscience. Because no similar courses have been offered anywhere, the lack of templates and precedents provided me an ideal opportunity to integrate knowledge from multiple disciplines. I compiled a reading list ranging from recent journal articles and book chapters to online debates among renowned scholars, and even materials from the “Interpersonal Dynamics” course (also known as the “touchy feely”) at Stanford Graduate School of Business. I also employed many games, demonstrations, simulations, “pair shares”, and small group discussions to cultivate an inclusive and interactive learning environment.

The second component was a series of workshops on “how to step into another person’s shoes,” where students examined various methods to cultivate empathy in life. For example, after reading a book chapter on how mental simulation connected people from diverse backgrounds, students worked in small groups to conceptually develop an “Empathy Museum,” where technology and media were used creatively and interactively to help museum visitors simulate different people’s life experiences. Below I am listing a few museum exhibits they proposed:

Although my course did not have the time and resources to implement and test the proposals, the “Empathy Museum” was a highly inspiring experience for students. It encouraged students to embrace their creativity and helped them identify their own interests. To diversify students’ learning experiences, I also invited guest speakers from Harvard Education School, Harvard Kennedy School, and the Symbolic Systems Program at Stanford to facilitate various workshops.

The final component was the “Action Plan,” where students designed their capstone projects to apply the knowledge and skills of empathy and leadership in their home communities. This project-based learning approach trained students to collect information over a very short period of time and provided an opportunity to incorporate their unique backgrounds, talents, and interests into our learning community. I have noticed that students were highly motivated by their peer students’ projects and became even more engaged in the classroom.

Assessing Student Learning and My Teaching

Assessing students’ learning progress and my effectiveness in teaching is critical. Depending on the situation and purpose, I like to use a variety of assessment methods to assess student learning.

For example, when I was discouraged to use formal tests and quizzes in my pre-college course, I embraced other data-driven assignments: I assigned students oral presentations and provided objective grading rubrics for clear and accurate evaluation; I regularly checked in with students with formal feedback forms as well as informal meetings; I also assigned students short essays to reflect on their personal development and their learning experiences and provided feedback.

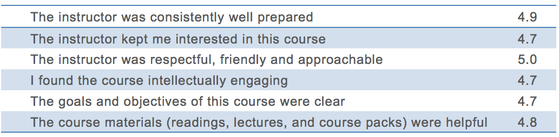

I received the 2015 Archambault Award for Teaching Excellence (honorable mention for teaching with distinction) from Brown University. In the award announcement, the committee noted that, “Her efforts resulted in a course that pushed students to think beyond themselves, learn what it means to be empathetic, how this is coupled with effective and valuable leadership and visualize themselves on the path to being leaders in their local community, region and indeed, one day, the world.” My course evaluations were also very positive (see Table 1). What really touched me, however, was over 30 thank-you letters I received after my course over two summers, in which students told me that they gained new knowledge and were determined to continue learning in related topics. This was a genuinely rewarding message from my students.

I believe that learning is fun, exciting, and rewarding; it opens eyes to the world, hearts to other people, and doors to the future. Over the past few years, I have had the privilege of designing my own learning experience and working with great teachers in psychology, anthropology, acting, persuasion, and organizational behavior. Genuinely inspired by my educational experiences, I would like to pass on the same spirit of learning to my students. I hope that students in my class will not only gain knowledge and skills in research and thinking, but cultivate curiosity about social phenomena and underlying mechanisms as well. Most importantly, my goal is that students gain a deeper understanding about their interests and passion, which will motivate them to continue self-guided learning long after graduating from my class.

The ability to conduct self-guided learning is especially critical to this generation of students. The rapid pace of technological advancement constantly poses new sets of challenges to our society, which go far beyond the issues researchers have investigated in the past. And for many problems, we do not have established theories, methods, or tools to solve them. As I expect my students to take on leading roles in various segments of our society, it is critical for them to learn how to effectively guide their own learning and solve unprecedented issues based on existing knowledge, skills, and available methods. To inspire them to become self-guided life-long learners, my teaching philosophy focuses on project-based learning, an interactive learning environment, and multi-disciplinary teamwork.

My Teaching Approach: “Leading with Empathy” as an Example

In Summer 2015 and 2016, I implemented my ideals of teaching and learning in my pre-college course at the Brown Leadership Institute, entitled “Leading with Empathy in the 21st Century”. This was a new course I developed and taught independently. Over two weeks in each summer, 25 high school students from all over the world spent 5.5 hours each day in my class to study the science of empathy and to cultivate empathy in themselves and in our interdependent society. The course consisted of three major components. The first one was academics: Students learned important concepts, theories, and research paradigms on empathy and leadership from social psychology and social neuroscience. Because no similar courses have been offered anywhere, the lack of templates and precedents provided me an ideal opportunity to integrate knowledge from multiple disciplines. I compiled a reading list ranging from recent journal articles and book chapters to online debates among renowned scholars, and even materials from the “Interpersonal Dynamics” course (also known as the “touchy feely”) at Stanford Graduate School of Business. I also employed many games, demonstrations, simulations, “pair shares”, and small group discussions to cultivate an inclusive and interactive learning environment.

The second component was a series of workshops on “how to step into another person’s shoes,” where students examined various methods to cultivate empathy in life. For example, after reading a book chapter on how mental simulation connected people from diverse backgrounds, students worked in small groups to conceptually develop an “Empathy Museum,” where technology and media were used creatively and interactively to help museum visitors simulate different people’s life experiences. Below I am listing a few museum exhibits they proposed:

- A role-playing video game (RPG) in which players control the action of a first-generation college student to navigate her college life;

- A “life simulation room” where people experience social scenarios varying from being bullied to being unconditionally accepted in an immersive display system.

- A “tech-free zone” where people put screens aside and play improvisation games together.

Although my course did not have the time and resources to implement and test the proposals, the “Empathy Museum” was a highly inspiring experience for students. It encouraged students to embrace their creativity and helped them identify their own interests. To diversify students’ learning experiences, I also invited guest speakers from Harvard Education School, Harvard Kennedy School, and the Symbolic Systems Program at Stanford to facilitate various workshops.

The final component was the “Action Plan,” where students designed their capstone projects to apply the knowledge and skills of empathy and leadership in their home communities. This project-based learning approach trained students to collect information over a very short period of time and provided an opportunity to incorporate their unique backgrounds, talents, and interests into our learning community. I have noticed that students were highly motivated by their peer students’ projects and became even more engaged in the classroom.

Assessing Student Learning and My Teaching

Assessing students’ learning progress and my effectiveness in teaching is critical. Depending on the situation and purpose, I like to use a variety of assessment methods to assess student learning.

For example, when I was discouraged to use formal tests and quizzes in my pre-college course, I embraced other data-driven assignments: I assigned students oral presentations and provided objective grading rubrics for clear and accurate evaluation; I regularly checked in with students with formal feedback forms as well as informal meetings; I also assigned students short essays to reflect on their personal development and their learning experiences and provided feedback.

I received the 2015 Archambault Award for Teaching Excellence (honorable mention for teaching with distinction) from Brown University. In the award announcement, the committee noted that, “Her efforts resulted in a course that pushed students to think beyond themselves, learn what it means to be empathetic, how this is coupled with effective and valuable leadership and visualize themselves on the path to being leaders in their local community, region and indeed, one day, the world.” My course evaluations were also very positive (see Table 1). What really touched me, however, was over 30 thank-you letters I received after my course over two summers, in which students told me that they gained new knowledge and were determined to continue learning in related topics. This was a genuinely rewarding message from my students.

Table 1. Student evaluation scores from Summer 2015 (1–strongly disagree; 5–strongly agree)

Previous Training in Teaching and Effective Communication

My successful instructor experience is a result of years of systematic training and preparation. I served as a teaching assistant to five undergraduate courses in the CLPS Department at Brown and one MBA elective at Stanford Graduate School of Business. These courses offered me comprehensive teaching assistant experiences in classes of various types and sizes, ranging from a 300-student lecture course to a 20-student lab course. As a teaching assistant, I actively engaged in all aspects of teaching, such as giving guest lectures, leading review sessions, grading exams and essays, creating exams, holding office hours, and supervising student independent research projects.

In fact, teaching did not come naturally to me. Naïvely thinking that teaching was simply an extension of research conversations, I did not start out very well, but each year I learned more about the craft of teaching. I also participated in a year-long training program at Brown Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, where I attended lectures and workshops on learning styles, course design, grading and assessment, inclusion and diversity, and effective public speaking and classroom behavior. To overcome the barrier of not being a native English speaker, I even took acting classes and persuasive communication classes in the Department of Theater Arts and Performance Studies. Over the past years, I have made steady progress in course evaluations on my overall effectiveness as a teaching assistant. My independent teaching, as illustrated earlier, then took an even more significant step up.

My successful instructor experience is a result of years of systematic training and preparation. I served as a teaching assistant to five undergraduate courses in the CLPS Department at Brown and one MBA elective at Stanford Graduate School of Business. These courses offered me comprehensive teaching assistant experiences in classes of various types and sizes, ranging from a 300-student lecture course to a 20-student lab course. As a teaching assistant, I actively engaged in all aspects of teaching, such as giving guest lectures, leading review sessions, grading exams and essays, creating exams, holding office hours, and supervising student independent research projects.

In fact, teaching did not come naturally to me. Naïvely thinking that teaching was simply an extension of research conversations, I did not start out very well, but each year I learned more about the craft of teaching. I also participated in a year-long training program at Brown Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, where I attended lectures and workshops on learning styles, course design, grading and assessment, inclusion and diversity, and effective public speaking and classroom behavior. To overcome the barrier of not being a native English speaker, I even took acting classes and persuasive communication classes in the Department of Theater Arts and Performance Studies. Over the past years, I have made steady progress in course evaluations on my overall effectiveness as a teaching assistant. My independent teaching, as illustrated earlier, then took an even more significant step up.